A new HBO documentary called ‘The Crime of the Century’ lays bare how firms like Purdue used bribery, dodgy marketing, and shady political deals to make fortunes by getting millions hooked on super-strong painkillers.

What would it look like if an illegal international drug cartel were allowed to advertise? Perhaps it might take the form of slick music videos and glossy magazine ads promising an ‘end to pain’. Certainly, they would minimise the negative effects of their drugs on your life, your future, and your loved ones. If questioned about what they were doing, we can imagine them blaming those who use their drugs, not themselves for providing them.

It sounds mad – madder still that anyone would believe them – but this is exactly what has been allowed to happen with large pharmaceutical companies and their marketing of highly addictive opioid drugs.

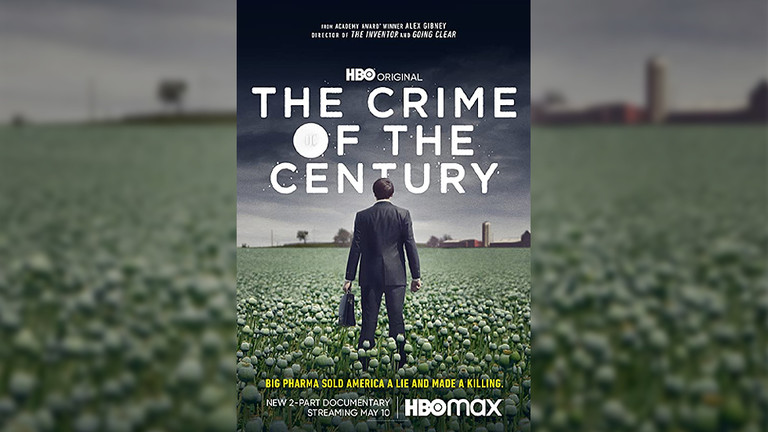

At least, this is the argument put forward in a new two-part HBO documentary series released this week entitled, ‘The Crime of the Century’. Across its nearly four-hour run-time, director Alex Gibney lays bare the bribery, underhanded marketing tactics, and shady political dealings that enabled the devastating overproduction and over-distribution of synthetic opiates. In devastating detail, the documentary portrays American pharmaceutical companies and the doctors who recklessly doled out prescriptions as elements of a glorified drug cartel – dealers in lab coats, suits and ties.

Systematically overselling the benefits of synthetic opioids and downplaying the risk of addiction, the documentary traces how drug companies are driven to pursue ever stronger and more exotic medications as patents on old treatments run out and profits dry up. In many ways, it traverses territory that is already well known, but is no less useful for highlighting in shocking detail just how much these companies have become a major risk to public health.

This is particularly true in their penchant for ‘discovering’ and treating ever more chronic conditions. While the efficacy of opioids for treatment of acute pain and end-of-life care has been well known, there is little incentive to develop and provide drugs solely for such patients, who tend to be few and far between and whose needs are often short-term. No, the real money is in long-term use in greater numbers. And this is where the dangers of pushing these drugs on patients with any kind of pain became increasingly clear.

Through heart-rending stories of suffering and loss, Gibney adeptly shows how a deadly cocktail of business incentives to push for over-prescription at escalating doses, inherent addictiveness, and, in some cases, communities facing economic despair, combined to produce the ‘perfect storm’ that became the opioid crisis.

In one story, a former heroin addict details his experience being used as a human guinea pig, prescribed a daily dose of pills equivalent to 200 hits of heroin. In another, a victim whose family described her as living a happy, functional life using nothing more than Tylenol was prescribed high doses of a range of opioids and muscle relaxants that regularly rendered her unconscious. One day her husband found her dead next to a phone that she’d attempted to use to call for help.

What could possibly fuel such enormous failure of caution? The obvious answer is greed and profit. Indeed, the meagre payouts and settlements companies like Purdue Pharma were ordered to pay over the years paled in comparison to the eye-watering profits they made misrepresenting their drugs. But the story is much deeper. The ‘opioid epidemic’ itself was preceded by claims that most Americans were actually being undertreated. What is more, they were being left callously to suffer in an ‘epidemic of pain’. Throughout the series, company representatives and even policymakers refer over and over to a ‘growing epidemic’ of pain suffered by millions.

This is what prepared the ground for the epidemic of over-prescription, permitting claims detailed in the documentary like “chronic pain patients can’t be addicts”, and the development of pseudoscientific terms like ‘pseudoaddiction’. The latter reflects an attempt to assuage the growing fears of prescribing physicians that the person before them is indeed becoming addicted to the drugs they were being prescribed. No, they only appear this way because they are in so much pain. You must help them. Prescribe more.

And prescribe more they did.

While it is easy to blame this situation on the greed of companies like Purdue Pharma and the owning Sackler family that lived luxuriously in its shadow, they would not have found such a ready market had they not been able to feed and exploit a culture with a preexisting aversion to pain. Indeed, many of the physicians and sales executives responsible for pushing large doses of highly addictive pain medications justified their actions with their belief that a life with pain was a life not worth living. They had convinced themselves that any pain was worse than death.

Supplanting everything that once made life meaningful, the pursuit of health and even mental health have become ultimate goals. The notion that one might tolerate pain, whether physical or psychic, is seen as beyond the pale. It is no longer, ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.’ Any pain or negative experience is seen as intensely damaging to the human psyche.

In a life without meaning, any pain becomes unbearable. We all become patients in waiting. Easy targets for these drug dealers in suits and ties.